By Andrew Brandt and Curtis Fechner

It’s appropriate that this year’s Blizzcon, the two-day celebration of all things World of Warcraft, takes place during National Cyber Security Awareness Month. No other game is as heavily targeted by thieves as WoW, so we thought this would be as good a time as any to run down some of the malware threats that face gamers. 2010 has been a big year for Trojans that steal game passwords or license keys.

It’s appropriate that this year’s Blizzcon, the two-day celebration of all things World of Warcraft, takes place during National Cyber Security Awareness Month. No other game is as heavily targeted by thieves as WoW, so we thought this would be as good a time as any to run down some of the malware threats that face gamers. 2010 has been a big year for Trojans that steal game passwords or license keys.

The people who create malware targeting online games show no signs of relenting, nor are they laying down on the job. Innovation is the name of the game, and password-stealers this year innovated their infection techniques to make them more effective and even harder to detect.

Two-factor authentication tokens, such as the Blizzard Authenticator, do a great job of preventing fraud. If you play WoW, the seven or so bucks the Authenticator costs can prevent a lot of headaches if your account becomes compromised by either a Trojan or a phishing Web site. The Authenticator displays a series of numbers that change about once a minute, and a gamer needs to enter these numbers along with a username and password to play the game.

However, while gamers who play Blizzard’s games might find themselves at reduced risk of phishing thanks to the Authenticator, other companies that operate the kinds of massively-multiplayer games most targeted by phishing pages and malware are also targets for theft, and don’t yet offer an equivalent method of securing login credentials.

One technique that emerged this year ties the malicious keylogger to one or more of Microsoft’s DirectX libraries. DirectX is the engine in Windows that most 3D games use to render graphics, play sound effects, and manage game controllers. Trojans that hook into DirectX always load when DirectX is in use, and since DirectX is always loaded when you play a game, it means the “sleeper cell” game phishing Trojan doesn’t wake up and do its job until you’re playing a game. We published a definition in May, Trojan-PWS-Cashcab, which defeats this technique, and you can also simply reinstall DirectX over the top of itself to break the infection.

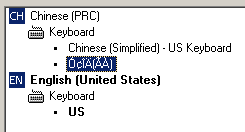

Another technique that was rarely used before this year is for the keylogger to replace the Input Method Editor (or IME) on the infected computer. The IME acts as a map for the keyboard, but is particularly important in Asian languages where the number of characters far exceeds the 104 keys on a typical keyboard. Japanese, Chinese, Korean, or other non-Latin alphabet characters may require two or more keypresses, and the IME interprets those keystrokes to generate the correct character.

If you’re interested in stealing passwords, putting a Trojan in the middle of the software which interprets keystrokes makes a lot of sense. A Symantec paper from 2005 predicted the use of bogus IMEs for keystroke logging, but the technique hasn’t been widely used until recently. Since most game phishing Trojans originate in China, it’s not hard to see why spies like the ones detected by our Trojan-PWS-IMEsneak definition seem to be getting distributed with increasing frequency by Chinese game phishers.

One sample of an unknown downloader I ran earlier this week serves as a perfect example: It contacted a server in China, retrieved a list of 24 programs stored on another server (also in China), then downloaded and executed them one by one. Of the 24 programs that were downloaded, 17 installed registry keys and other payload files that we detected with our IMEsneak definition. The rest installed their keystroke monitoring software as services, or attached themselves to Internet Explorer.

And Windows-based games aren’t the only targets for phishers. This year we saw a spike in the number of phishing Web pages that use, as a lure, the promise of hundreds or thousands of points for players of Xbox Live. All you need to do is enter your Xbox Live credentials into a Web page. As you can predict, this won’t end well.

Bottom line, gamers remain a highly-targeted category of Internet users, and must train themselves to treat as suspect any executable code, including “cheat” programs, key generators, and pirated copies of games themselves. I’d also like to see more cooperation, collaboration, and sharing of information between game publishers and the security industry. Both sides have a lot to offer the other, but so far the track record for collaboration hasn’t been all that great.