NOTE: This blog post discusses active research by Webroot into an emerging threat. This information should be considered preliminary and will be updated as more data comes in.

New variants of Locky—Diablo and Lukitus—have surfaced from the ransomware family presumed by many to be dead. After rising to infamy as one of the first major forms of ransomware to achieve global success, Locky’s presence eventually faded. However, it appears this notorious attack is back with distribution through the Necurs botnet, one of the largest botnets in use today.

Webroot protects against Diablo and Lukitus

We first detected Diablo on August 9, 2017, and Lukitus yesterday, August 16. Since then, we’ve seen activity hitting Windows XP, Windows 7, and Windows 10 machines in the United States, United Kingdom, Italy, Sweden, China, Botswana, Russia, Netherlands, and Latvia.

How are these attacks deployed?

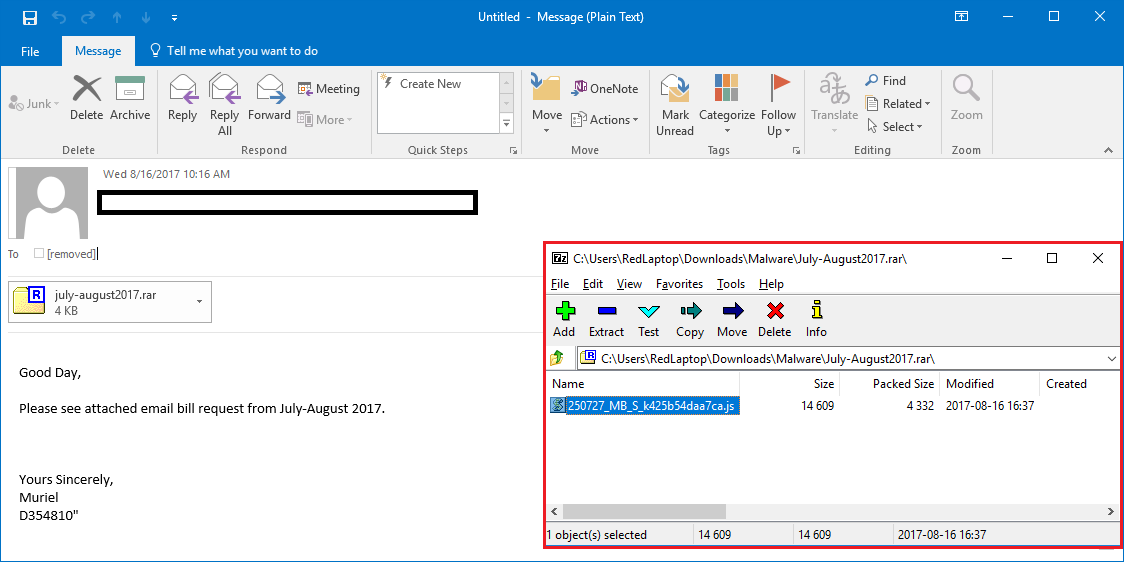

As with previous versions, the initial attack vector is through malspam campaigns in which phishing emails contain a zipped attachment with malicious javascript that downloads the Locky payload.

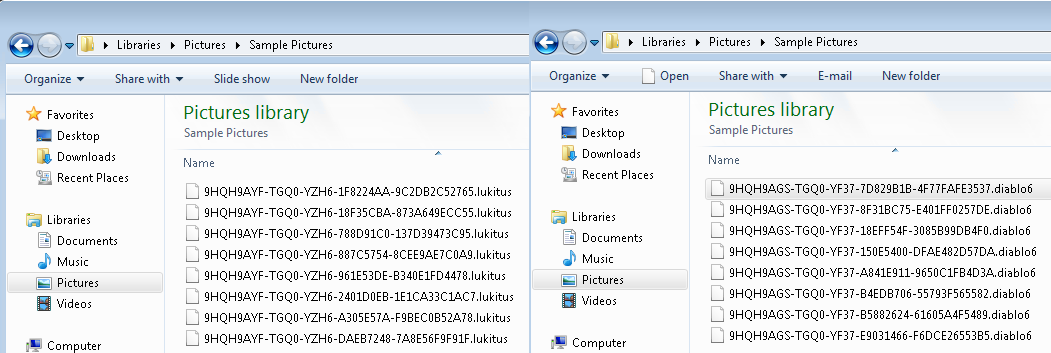

Once the Locky payload is dowloaded, it encrypts the users’ files with “.diablo6” and “.Lukitus”, respectively.

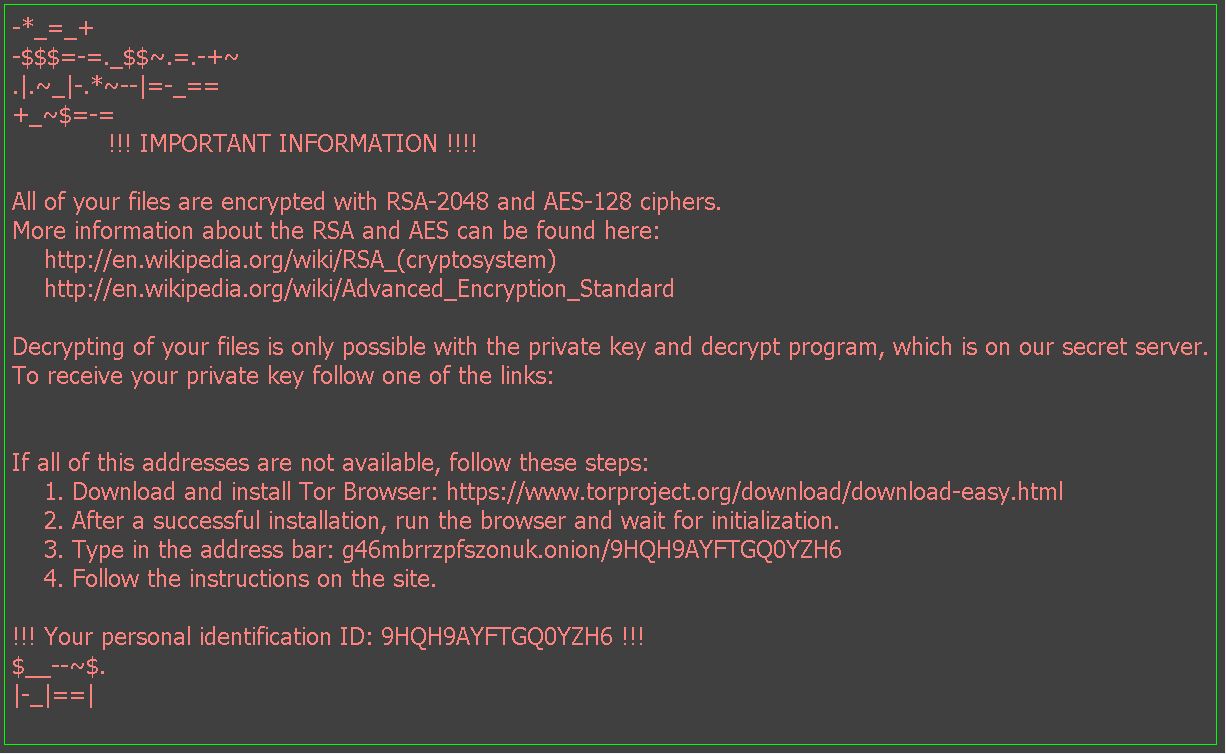

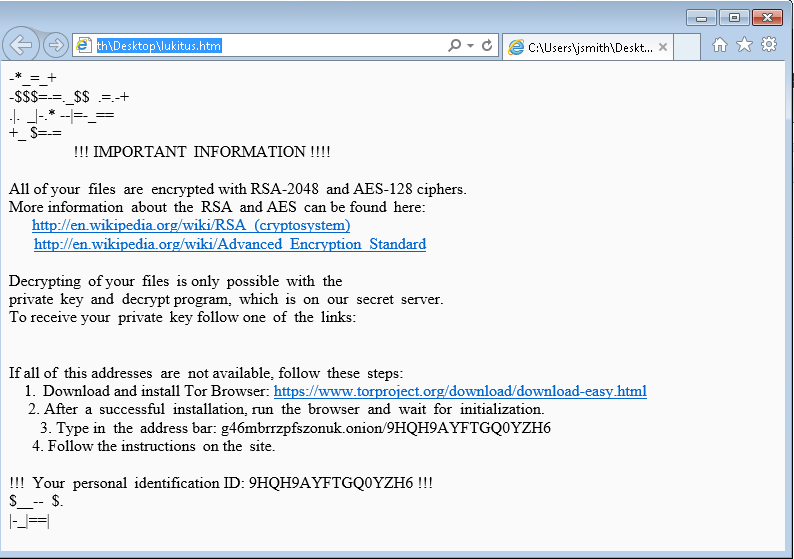

Then it changes the desktop background and provides the rescue pages “diablo6.htm” and “lukitus.htm”, which are identical.

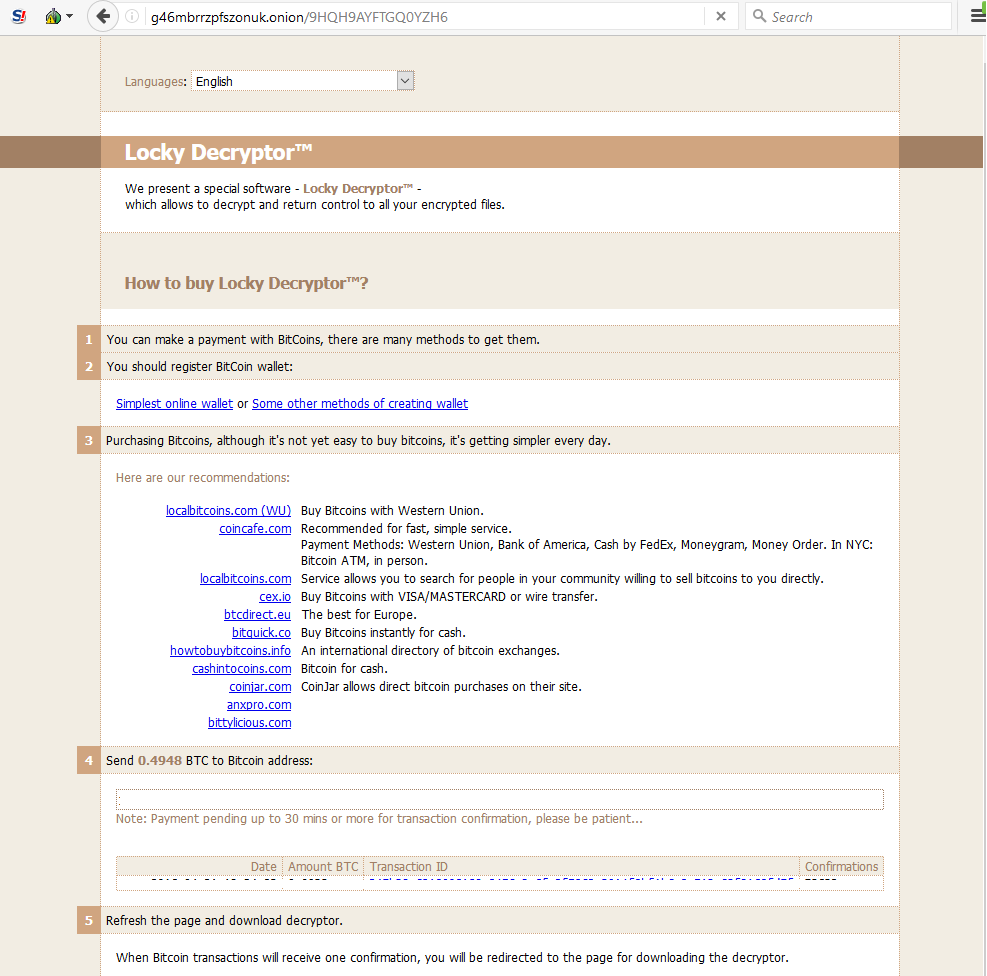

Following what’s been standard for years, the Locky ransomware instructs the user to install a Tor Browser, then navigate to your unique .onion address to pay the ransom.

There is currently no available decryption tool that will work, other than paying the ransom to obtain the decryption keys. Although Webroot will stop this specific variant of Ransomware as a Service in real time—before any encryption takes place—don’t forget that the best protection in your anti-ransomware arsenal is a strong secure backup. You can use a cloud service or offline external storage, but remember to keep it up to date for personal productivity and business continuity.

For best practices for securing your environment against encrypting ransomware, see our community post.

Initial list of MD5s analyzed by Webroot

NOTE: This exhaustive list is current as of publication of this blog. We will continue to update internal lists but will not publish further additions until such time that we deem it necessary.

2E1A3A5F24AA6D725405E009949E6F0B

7821C8F49773EC65B9DFE8921693B130

544BC1C6ECD95D89D96B5E75C3121FEA

A2AEC1429D045355098355CAA371F23E

4779E473C909104272853EA1313BEE37

D7D22FFB1E746C20828422DA5CDF93DA

5245A7FA2351212EBF8257C55536791D

FE1CBC72C53AE7D8D16A5C943B5769FC

EA1832B7539BE8F265C08C0075CCB4DE

ACEA79268714A4752E3BF22161B90471

4BAA57A08C90B78D16C634C22385A748

0816080383AB3F33FEB9B6B51E854C73

0E05A7B9F1F2A19B678D2D92ABF70E47

F83DDED266CA056804BCC60EB998FA6C

4938F1D87F52473BC13C88498D6FC7AF

4BAA57A08C90B78D16C634C22385A748

F83DDED266CA056804BCC60EB998FA6C

8009E4433AAD21916A7761D374EE2BE9

E7E5628F67CB2FA99A829C5A044226A4

4BAA57A08C90B78D16C634C22385A748

3506AB24DB711CF76F95F89B4990981A

ECDAFEF0E38D2B5F24B806AF4FD54CC6

89ED8780CAE257293F610817D6BF1A2E

E613CF78955A4C1D8732B0ECB202CAEC

45021A1A159DEA9952AD3494B8D49852

993608B9AEA2B351E4BA883FEE8916B0

FBE9106026AF42CD24AB970ED718A579

23CCA546A85B5CAA12441F7F4C6B48E4

01DA2F592A64F2ABA0986319436177A5

96E214BAF7F26B879BAF0D87D830F916

040C537F575ED64374AB7F38F27E03F1

D3C856485116A09CAA37D867561BD634

BA82AA75BF6FC2549049877ACE505A24

9C6F2921CE536393198C605C15AE8C91

941CDFF8A86E56D11FCAF25CF7C2129B