Rogues Impersonate Google, Firefox Security Alerts

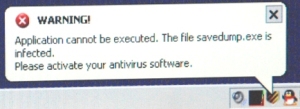

In the past week, we’ve begun to see new fakealerts — those disturbingly effective, entirely bogus “virus warning” messages — that appear to impersonate the appearance and text of legitimate warning dialogs you might see while surfing with the Firefox browser, or searching Google. The dialog, in a stern, red dialog box on a gray background, reads “Warning! Visiting this site may harm your computer!” — a dialog that appears to be designed to evoke the look of a Google’s Safe Browsing advisory as displayed in Firefox.

In the past week, we’ve begun to see new fakealerts — those disturbingly effective, entirely bogus “virus warning” messages — that appear to impersonate the appearance and text of legitimate warning dialogs you might see while surfing with the Firefox browser, or searching Google. The dialog, in a stern, red dialog box on a gray background, reads “Warning! Visiting this site may harm your computer!” — a dialog that appears to be designed to evoke the look of a Google’s Safe Browsing advisory as displayed in Firefox.

Cast as a kind of split between a warning message and a clickwrap agreement, the text of the dialog box reads “This web site probably contains malicious software program, which can cause damage to your computer or perform actions without your permission. Your computer may be infected after visiting such web site. We recommend you to install (or activate) antivirus security software.”

At the bottom of the dialog box, two buttons, labeled “Continue Unprotected” and “Get security software” are preceded by the sentence “I do realize that visiting this site can cause harm to my computer.” I’d give them points for honesty, but I’d rather not give them points for anything.

Nothing happens when you click the “Continue Unprotected” button, and I’ll give you one guess what happens next when you click the “Get security software” button.

Steam Users Targeted by Phishers

A phishing campaign that started around the beginning of the year, targeting gamers who use Valve Software’s Steam network, continues unabated but with a twist: The phishers have registered dozens of domain names, such as trial-steam.tk or steamcommunity###.tk (where the ### can be a two or three digit number), which are used to host the phishing pages. The pages appear to be a “Steam Community” login page which looks identical to Valve’s Steam Community Web site.

A phishing campaign that started around the beginning of the year, targeting gamers who use Valve Software’s Steam network, continues unabated but with a twist: The phishers have registered dozens of domain names, such as trial-steam.tk or steamcommunity###.tk (where the ### can be a two or three digit number), which are used to host the phishing pages. The pages appear to be a “Steam Community” login page which looks identical to Valve’s Steam Community Web site.

There are a few ways you can quickly identify whether you’re on the right page, or a fake. For one, the real Steam Community page is a secure HTTP page, so you should see the “https” in the address bar, and the lock icon in the corner of the browser window. By clicking on this icon, you can view the valid security certificate information, which clearly shows that the site is owned by Valve.

Another way you can tell that you’re on the correct Steam login page is to try using the “Select your preferred language” dropdown at the top of the window to change to any language other than English. If you’re on Steam’s page, the language will change; If you’re on the phisher’s page, it simply refreshes and remains set to English, no matter which language you pick. Also, the real Steam page features a cartoony graphic of “players” chatting amongst themselves which changes periodically. The phishers’ pages always have the same static graphic, shown above.

Read on for some additional details.

Trojans Replace Windows System Files

When the threat research analysts here at Webroot recently started seeing malware swapping out legitimate components of Windows and replacing them with malware payloads, I couldn’t help but wonder what these malware authors were thinking.

When the threat research analysts here at Webroot recently started seeing malware swapping out legitimate components of Windows and replacing them with malware payloads, I couldn’t help but wonder what these malware authors were thinking.

After all, cybercriminals with a lick of sense know very well that messing with system files is dangerous juju. Such an act could, in the right (or should I say wrong) circumstances, render a PC inoperable, or at the very least, bogged down in crashes and instability. And for the authors of phishing malware, it would be incredibly thick-headed to do something to an infected system which might alert the user that something is wrong. After all, when it comes to stealing passwords, flying under the radar is the goal, otherwise the owner of the infected machine might hunt down the problem and remove the Trojan before it has a chance to do its work.

Well, it’s probably a good idea never to underestimate the stupidity of some malware authors. In the past four months, we’ve created new definitions for two phishing Trojans — Trojan-PWS-Mockworthy and Trojan-Phisher-Cassicant — that routinely replace system files with their own malicious payload. Removal is incredibly easy, but generates error messages on the system. That’s just annoying. The best news is, you don’t even need an antivirus product to restore a system file that’s been replaced in this way: A system sweep will remove the malicious components, and a service called Windows File Protection will find the correct system file on your Windows CD and replace it for you. Read on for some step-by-step instructions on just how to do that.

More Malware Trades on Tawdry Searches

By now, you’ve most likely heard about how an ESPN reporter was victimized, and that a surreptitiously recorded video was distributed online. You may also have read that malware distributors were taking advantage of the high level of interest in this video to rapidly disseminate malware by convincing people to click links to malicious Web sites, including a fake CNN lookalike site, to watch said tawdry video.

By now, you’ve most likely heard about how an ESPN reporter was victimized, and that a surreptitiously recorded video was distributed online. You may also have read that malware distributors were taking advantage of the high level of interest in this video to rapidly disseminate malware by convincing people to click links to malicious Web sites, including a fake CNN lookalike site, to watch said tawdry video.

Well, that first wave of malware was almost identical to the distribution we saw when Farrah Fawcett died a few weeks ago. Web surfers were urged to click a link to download a picture of the late actress, and instead received an executable file which dropped, then downloaded, additional malware. Graham Cluley, who works for Sophos, pretty much nailed the story on his blog.

In our own research, we found the same things going on that he did: The piece of malware he describes (which we call Trojan-Downloader-Dermo) primarily engages in massive clickfraud, in which affiliates of advertising networks are paid each time someone clicks an advertisement in their browser. The software, in this case, is directed to “click” through hundreds of ads per minute. Occasionally, those “ads” exploit vulnerabilities in the browser to foist more malware onto the victim’s machine.

But the malware distribution didn’t stop there. Seizing on the opportunity, another bunch of creep distributors of rogue antivirus products also began spreading the pain, using terms like “peephole video” to rank themselves high in search results. What we found was a rogue that not only lies about alleged infections on the victim’s computer, and features supposed endorsements from legitimate, respected technology publications — the award logos of PC World (and its UK counterpart PC Advisor), PC Magazine, and C|Net’s Computer Shopper grace its website — but spreads via a PDF file which exploits a relatively recently-disclosed vulnerability in Adobe’s Acrobat Reader software.

But the malware distribution didn’t stop there. Seizing on the opportunity, another bunch of creep distributors of rogue antivirus products also began spreading the pain, using terms like “peephole video” to rank themselves high in search results. What we found was a rogue that not only lies about alleged infections on the victim’s computer, and features supposed endorsements from legitimate, respected technology publications — the award logos of PC World (and its UK counterpart PC Advisor), PC Magazine, and C|Net’s Computer Shopper grace its website — but spreads via a PDF file which exploits a relatively recently-disclosed vulnerability in Adobe’s Acrobat Reader software.

Oh, Hush Chicken Little – The Sky is Not Falling: Why Cloud Security is Still Safe

By Brian Czarny

This week it was impossible to escape the “big news” that Twitter got hacked. The French hacker, known as “Hacker Croll,” who made headlines back in May for a similar Twitter breach, was at it again. This time he managed to get his hands on at least 310 sensitive Twitter business documents by gaining access to an employee’s email account, subsequently using information found in that account to then access the employee’s Google Apps account to steal the confidential company documents. The hacker sent the documents to TechCrunch, who then chose to publish them along with an account of the breach.

This highly publicized breach got people talking, and ignited a wave of speculation about two things: first, about the security of passwords and how easy it is to guess the answer to someone’s security question based on publicly available information found on social media sites; and second, about the security of data stored “in the cloud” – in this case, Google Apps.

Oh no, the sky is falling!

Our data isn’t safe in the cloud!

On the second point, let’s not take this too far. This incident has little to do with the security of the cloud apps themselves. It is much more about the first point and the security practices that users of all Web sites and applications – whether they are banking sites, social media sites or cloud applications – should be employing in their day-to-day use.

The key learning end users should take from this incident is that password security is critical, both in terms of the passwords you choose as well as the amount of data you expose publicly through social media sites like Twitter and Facebook.

Twitter spells this out on its blog response and even Hacker Croll himself articulates that his intention is to teach people a lesson about the security holes in secret questions:

“What I would like to say is that even the biggest and the strongest do silly things without realizing it and I hope that my action will help them to realize that nobody is safe on the net. If I did this it’s to educate those people who feel more secure than simple Internet novices. And security starts with simple things like secret questions because many people don’t realise the impact of these question on their life if somebody is able to crack them.”

What Keeps IT Professionals Up at Night

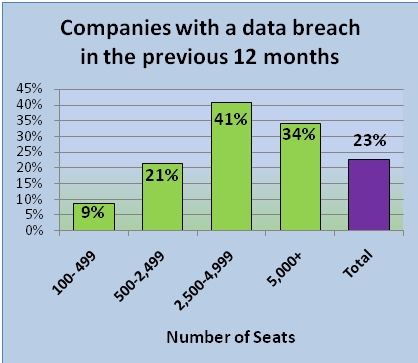

Webroot recently surveyed more than 300 email and Web security professionals about email management, compliance, archiving, encryption, spam, viruses, Web filtering and Web-based malware attacks. Our research shows that security practices and risk perceptions have evolved over the last year – the top three security concerns are email threat protection, data security/confidentiality and Web threat protection. Other highlights of the survey include:

- Security professionals are clearly worried about insufficient resources for Web security– a potential result of the economic downturn.

- The large number of organizations that were required to retrieve email for legal or compliance reasons within the last year indicates that email archiving services are becoming increasingly important.

- Most companies experienced some type of negative impact due to Web-based threats over the last 12 months, ranging from server outages and disrupted business activities to compromised data or transactions.

- 23% of survey respondents experienced a data breach – which cost between $10,000 and $1 million:

Just two weeks ago, Heartland Payment Systems disclosed that intruders hacked into the computers it uses to process 100 million payment card transactions per month for 175,000 merchants in one of the largest breaches on record. This past April, the Virginia Department of Health Professions learned that its Prescription Monitoring Program (PMP) computer system had been accessed by an unauthorized user – who then demanded $10 million to return over 8 million patient records and 35 million prescriptions.

As previously reported on this blog, Web threats are growing at a rapid pace in both volume and sophistication – fueled by the financial motivation of cybercriminals. Our research also showed that email threats were the top concern of IT professionals – but while email protection is important, the new vector of attack is the Web – and only 15% of organizations reported having Web security measures in place while 85% of new malware originates via the Web.

AutoCAD Adware Trojans Target Techies

Every once in a while, you hear whispers or rumors about specially-crafted, targeted malware designed to steal a specific piece of data from a particular victim. The data thieves, in these limited cases, tend to be clever, thoughtful, and methodical in both the creation and deployment of their creations.

Every once in a while, you hear whispers or rumors about specially-crafted, targeted malware designed to steal a specific piece of data from a particular victim. The data thieves, in these limited cases, tend to be clever, thoughtful, and methodical in both the creation and deployment of their creations.

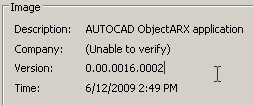

Rarely do malware researchers encounter these files. But it does happen occasionally, and I thought I had stumbled upon one of these kinds of spies a few weeks ago. It’s a peculiar Trojan horse which has been written not as a standard Windows application, but as an ObjectARX application — an application which can only run if you have AutoCAD, the engineering and design program from AutoDesk, installed on your PC.

Now, why do you suppose a malware author would write a Trojan that can only run on computers with AutoCAD; a Trojan that is so well designed that it prevents antivirus applications from running, and downloads specific, tailored updates for itself, depending on which version of AutoCAD the victim has on his or her PC?

Sounds a lot like a slick tool for corporate espionage, right? Well, not quite. Fark: It’s just another stupid adware client. We’re calling this dumb gimmick Trojan-Pigrig.

Jackson/Fawcett Malware is Extortion-ware

As I reported yesterday, searches for information about the deaths of Michael Jackson or Farrah Fawcett were turning up links to malware. This came as no surprise to anyone, though the speed with which the links spread was astonishing: Within minutes of the first confirmation that Jackson had succumbed to a heart attack, the first malicious blog posts began popping up in search results. We’re continuing to monitor hundreds of malicious sites touting news of Jackson’s demise — and new malicious blogs are coming up as fast as the blog services can shut them off.

As I reported yesterday, searches for information about the deaths of Michael Jackson or Farrah Fawcett were turning up links to malware. This came as no surprise to anyone, though the speed with which the links spread was astonishing: Within minutes of the first confirmation that Jackson had succumbed to a heart attack, the first malicious blog posts began popping up in search results. We’re continuing to monitor hundreds of malicious sites touting news of Jackson’s demise — and new malicious blogs are coming up as fast as the blog services can shut them off.

The first site we encountered that referenced Jackson appeared to be a personal blog post hosted on Google’s own Blogspot service. However, we quickly determined that something wasn’t right with the post. Just visiting the page spawned a tornado of background and foreground browser activity — over 100 URLs, mostly called from ad-host Yieldmanager by an automated script hosted elsewhere, were pulled down in just the first three seconds after the page loaded; The list grew to 500 URLs by the time 32 seconds had elapsed.

To illustrate the speed that the scripts embedded in the malicious blog post were loading ads, I captured this short video, which shows the amount of activity in about 60 seconds of permitting the page to load. I can only guess that the volume of URLs was limited by the fact that I had to click through some dialog boxes that appeared during the test. Another interesting thing is that between the time I began the video and the time it ended, Google had terminated the malicious blog account — for the moment, at least. The last page to load in the video is a Google ‘404’ error message when I attempted to load the initial page a second time.

[vimeo http://vimeo.com/5329574]

Some of the sites loaded by these malicious scripts also used browser exploits to damage the test system.

Our Cup Runneth Over with Farrah Fawcett Files and Michael Jackson Malware

With the sad news circulating the globe that 70s sex symbol, TV pitchwoman, and former Charlie’s Angel Farrah Fawcett passed away this morning, it didn’t take long for the malware vultures to execute their attack.

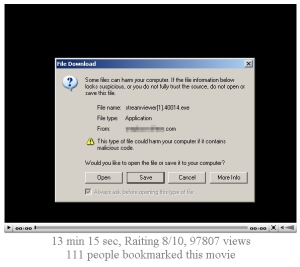

Beginning in the afternoon, our Proactive Research team began finding tons of pages that purportedly offered a Farrah Fawcett poster or photo for download. What you got, when you clicked the link that looks suspiciously like a video player (not a static image), was — you guessed it. A load of junk.

Interestingly, hovering the mouse over the video link causes the browser to display a “preview image” that looks awfully like Google’s front door. But clicking the link to the video brings you to yet another page with something that looks like a video player, and only when you click that link do you end up with an executable on your desktop.

Few antivirus companies have the malware in their definitions. We’re identifying the files pulled down by the Fawcett installer as Trojan-Cognac (they leave, shall we say, a distinctive aftertaste), as well as Trojan-Zoeken and Adware-Sabotch. Zoeken is a nasty downloader, which brings down all kinds of badness on an infected system, and Sabotch tends to tout those wonderful rogue antivirus products we all love so much.

Few antivirus companies have the malware in their definitions. We’re identifying the files pulled down by the Fawcett installer as Trojan-Cognac (they leave, shall we say, a distinctive aftertaste), as well as Trojan-Zoeken and Adware-Sabotch. Zoeken is a nasty downloader, which brings down all kinds of badness on an infected system, and Sabotch tends to tout those wonderful rogue antivirus products we all love so much.

So far, the Fawcett-related malware is all coming from fake pages set up on blog site Vox.com. Until they clean up this mess (which I imagine will be fairly time consuming, as new ones keep popping up), don’t follow any search links headed in their direction.

And this afternoon, as rumors began to circulate that Michael Jackson was ill in hospital, the jackals pounced on that bit of news. More on that in the next post.

Drive-by Downloads Still Pack a Punch – If You Click

In the course of surfing around, looking for ways to get infected, I stumbled upon a site that offers visitors downloads of key generators, cracks, and other ways to circumvent the process used by most legitimate software companies to prevent people who didn’t pay for the software from registering or using it.

In the course of surfing around, looking for ways to get infected, I stumbled upon a site that offers visitors downloads of key generators, cracks, and other ways to circumvent the process used by most legitimate software companies to prevent people who didn’t pay for the software from registering or using it.

And of course, I stumbled into a morass of malware.

Well, “stumbled” isn’t entirely accurate. The site is well-known to us as a host of drive-by downloads — it’s a site that uses browser exploits to infect your computer. But I went there anyway just to see what they’re driving-by with these days. Technically, the site didn’t burn us — it came from an advertising network, which loaded a script that bounced to three separate machines before landing my test PC in the hot seat. Cold comfort if your PC happens to get slammed with this junk.

Gamers: Fight the Phishers

Last week, I posted a blog item that explained how gamers face a growing security threat in phishing Trojans — software that can steal the passwords to online games, or the license keys for offline games, and pass them along to far-flung criminal groups. We know why organized Internet criminals engage in these kinds of activities, because the reason is always the same: There’s a great potential for financial rewards, with very little personal risk.

Last week, I posted a blog item that explained how gamers face a growing security threat in phishing Trojans — software that can steal the passwords to online games, or the license keys for offline games, and pass them along to far-flung criminal groups. We know why organized Internet criminals engage in these kinds of activities, because the reason is always the same: There’s a great potential for financial rewards, with very little personal risk.

So I thought I’d wrap up this discussion with some analysis of how the bad guys monetize their stolen stuff. After all, how do you fence stolen virtual goods? And knowing that, is there a way to put the kibosh on game account pickpockets?

read more…

If You’ve Got Game, Phishers Want Your Stuff

Since the beginning of the year, my colleagues in the Threat Research group and I have been researching an absolutely astonishing volume of phishing Trojans designed solely to steal what videogame players value most: the license keys that one would use to install copies of legitimately purchased PC games, and/or the username and password players use to log into massively multiplayer online games, such as World of Warcraft.

Since the beginning of the year, my colleagues in the Threat Research group and I have been researching an absolutely astonishing volume of phishing Trojans designed solely to steal what videogame players value most: the license keys that one would use to install copies of legitimately purchased PC games, and/or the username and password players use to log into massively multiplayer online games, such as World of Warcraft.

I can only imagine that it takes very little effort for the jerks behind this scheme to retrieve thousands of account details. (We began covering this issue briefly last week.) With such an effortless infection method, and the difficulty of prosecution (let alone identifying the perps), they don’t even seem to be concerned in the slightest about covering their tracks.

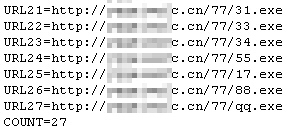

These single-purpose Trojans are very good at what they do, and can rapidly (and silently) report the desired information back to servers — typically, perhaps unsurprisingly, located in China. We know the exact servers they contact, and what kinds of information they’re sending. And we know why: Thar’s gold in them thar WoW accounts, and the rush is on to cash in.

Today, I’m going to go deeper into how the infections happen.